#ThrowbackThursday: WITCHES, MIDWIVES, AND NURSES

This fall, our archival intern Monika Zaleska will offer a glimpse back into FP’s collection, using correspondence, documents, and clips from our extensive archive. Monika is a PhD student in the CUNY Graduate Center’s Comparative Literature Program, and is working with FP through a grant from Publics Lab.

You can follow her on Twitter at @myszka_mz and check out her weekly posts here and on the FP instagram.

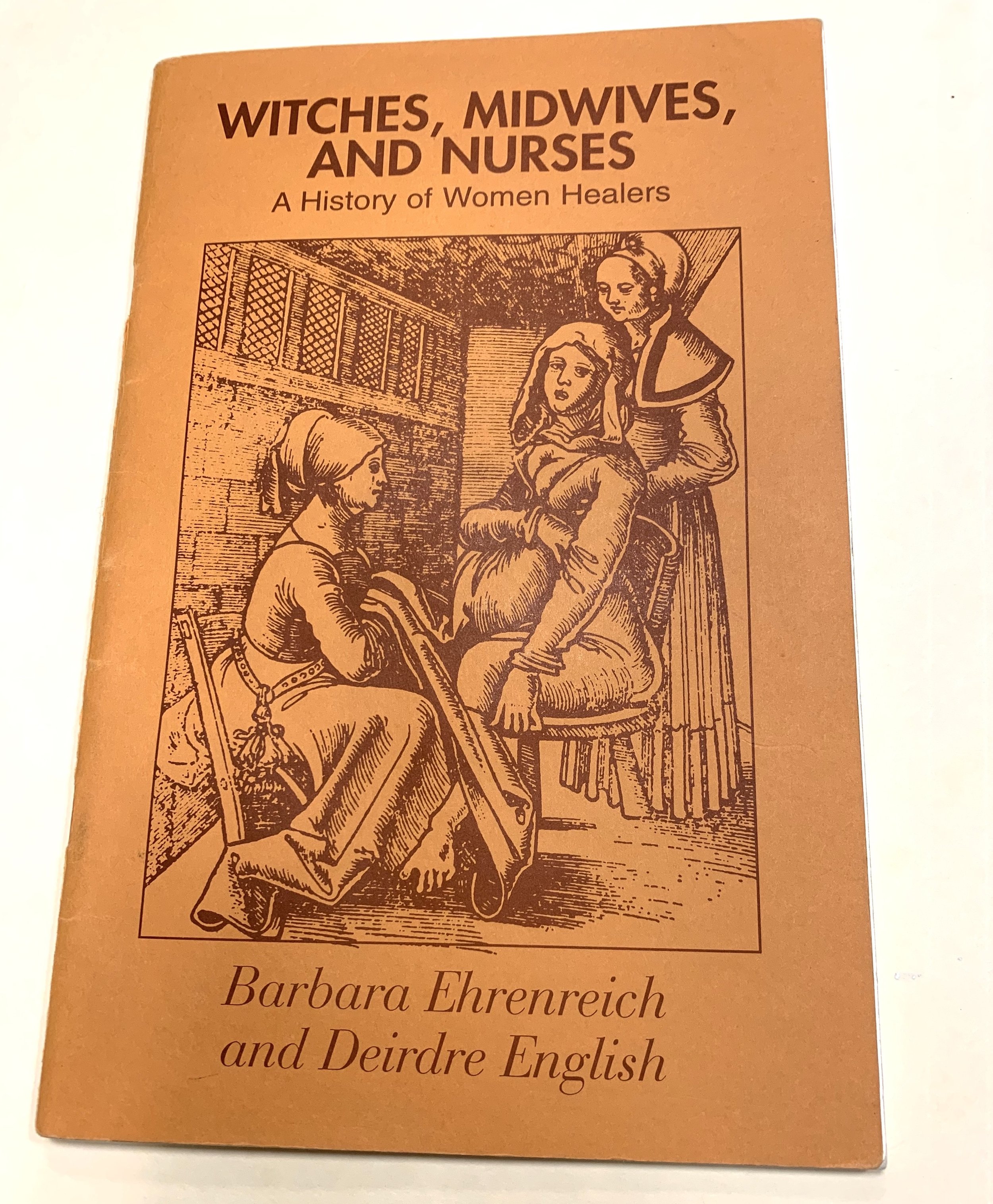

This week in the archives, I tackle an FP classic, so popular it’s been published around the world, from Poland to Brazil: Witches, Midwives and Nurses by Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English. Their pamphlet on the history of women healers was called a bestseller by The Village Voice when it was first published in 1973. It was reissued by FP in 2010 with a new introduction by the authors.

First published by their own small press, Glass Mountain Pamphlets, Ehrenreich and English sought to educate women on their forgotten place as healers.

We have not been passive bystanders in the history of medicine. The present system was born and shaped by the competition between male and female healers. The medical institution in particular is not just another institution which happens to discriminate against us: it is a fortress designed to and erected to disclude us.

The pamphlet focuses on the persecution of women healers during the “witch hunting” of 16th century Europe as well as the male professionalization of the medical field in the 19th century. Once leaders in the medical field, knowledgeable in herbal remedies, assisting in childbirth, and gentle curatives, women healers were vilified, persecuted, discredited and locked out of the medical profession. Ehrenreich and English stress that this was not a natural course of events, but a systematic attempt to rewrite history, by men.

Their pamphlet-sized attempt at revising medical history, long before it was a common academic inquiry, proved so popular that FP heard from publishers around the world eager to reprint Witches, Midwives and Nurses. Some, as seen in the letter above, did not even wait for permission or pay royalties, they simply pirated the text for their own purposes!

Though Ehrenreich and English critique the professionalization and stagnation of the medical field into the roles of “doctor” and his subordinate female “nurse,” their text not only sheds light on those stereotypes, but continues to help shift the narrative. Above, a Japanese publisher hopes to use Witches, Nurses, and Midwives as an educational text in a journal of nursing.

Their pamphlet reminds me of another important text on the sociopolitical position of women throughout history, Caliban and The Witch, by Italian thinker Silvia Federici. She too posits that men made a deal with the church and upper classes, and sold women out to accumulate power and capital. To downgrade women’s social position, their formerly respected communal knowledge was discredited, and women themselves were persecuted into submission with claims of witchcraft and dark magic.

But women, equipped with community knowledge about herbal remedies, anatomy, and childbearing were often better educated in medical science than their male contemporaries, who defamed them while promoting church doctrine and pseudosciences like alchemy.

According to Ehrenreich and English, women’s medicine was, and has always been, the common people’s medicine. It’s no wonder small, independent, working-class publishers, like the above press in Italy, wanted to republish this pamphlet, and begin to reclaim the feminist roots of the medical field.

Monika Zaleska is a writer, translator, and PhD student in comparative literature at the CUNY Graduate Center. She has an MFA from Brooklyn College, where she served as fiction editor of The Brooklyn Review, and currently teaches in the English department.