Panpocalypse Week Seven: Archives

In the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, a queer disabled woman takes to biking through a shutdown New York City in search for the ex-girlfriend who broke her heart.

Click here for Week Six.

Archives

Many of my favorite photographers—Brassaï, Arbus, Touchette, and lately John Edmonds and Heji Shin—reveal hidden worlds or worlds overlooked by the sometimes white, straight, or able-bodied gaze.

At night before bedtime when I am often the saddest, I look at photos by Brassaï and watch documentaries that are part of the Netflix Pride series. This week I watch Crip Camp, Circus of Books, and A Secret Love.

I scroll through the Lex ads. I badly want connection.

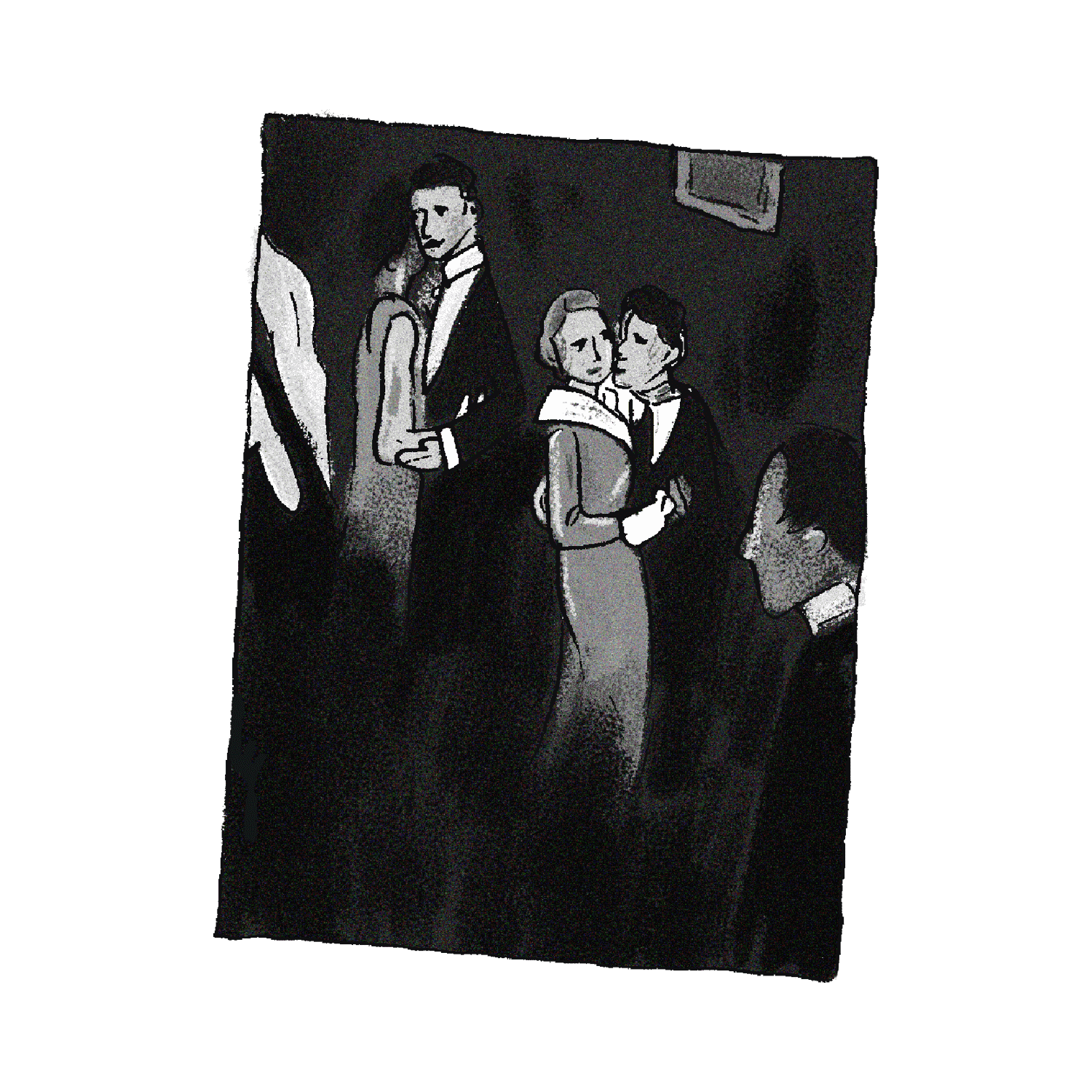

The Brassaï photo I keep returning to is awash in black, white faces emerging from the dark. Either very butch or very femme. Butch is a tuxedo, bowtie or necktie, sometimes a vest, short hair parted on the side, and the monocle, which in 1930s Paris was queer code. The femme women have set wavy hair, silk dresses, bare arms and shoulders, stockings, lipstick, plucked arched eyebrows. Cigarette smoke lingers in the dark. What pulls me, pricks me, shoots into my heart like an arrow—the punctum, as Roland Barthes calls it—is the couple dancing in the foreground. Their cheeks pressed together. The butch’s lips pressed to the femme’s cheek, whispering to her or kissing her. Hands clasped. Butch’s hand on the lower back of the femme. Such intimacy. Such closeness.

In A Secret Love, we meet Terry and Pat, who have been together for sixty-five years and have come out to their families in the last three years. These two, total babes even in their seventies, show me a kind of love I’ve not yet experienced. Long-lasting, partnered, enmeshed. There’s video footage of them skating, swimming, playing, laughing, dancing, working. It feels like a retrieval. The archive of lost queers. A correction. Their style and glamour. Unlike the lesbians at Le Monocle, able to hide in plain sight.

During much of the filming, Terry, who is also a former shortstop for the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League, is struggling with Parkinson’s. It’s a movement disorder, with some symptom overlap with my own, and I know the pain it causes. And then Pat is sick, and we see the two of them, Terry shaking next to Pat’s hospital bed, struggling to raise Pat’s hand to her lips. It takes effort and time, but she does it. Their conversation in this moment is so intimate, maybe the language of the bedroom, which is hinted at in photos throughout the movie.

Such a good little girl.

Who is my sweet little girl?

Are you going to be a good girl and eat?

That’s my sweet angel girl.

This is when my lips tremble. Later, I can’t sleep. All of the lost utterances in queer spaces. Cheeks pressed together. Hands holding. Whisperings, occasionally overheard, rarely recorded. I think of how Saidiya Hartman’s incredible history Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments achieves this too, another unearthing—this time of Black women and girls from 1890 to 1935. Hartman writes of her project:

The endeavor is to recover the insurgent ground of these lives; to exhume open

rebellion from the case file, to untether waywardness, refusal, mutual aid, and

free love from their identification as deviance, criminality, and pathology; to

affirm free motherhood (reproductive choice), intimacy outside the institution

of marriage, and queer outlaw and passions; and to illuminate the radical

imagination and everyday anarchy of ordinary colored girls, which has not

only been overlooked, but is nearly unimaginable. (xiv)

What a sentence! What a book! I don’t know why I need to tell you about these texts now, other than they are shaping me as I write and ride. I’m logging into the autofiction archive. I bring solitude, disability, illness, and love.

When I begin writing I am a girl with crayons and newsprint, later with a diary and a small matching pencil, and for most of my adult life, I write about girls and women. The girl is the forgotten one, so easy to dismiss. But the girl is everything.

Pothole

I try to keep up with the protesting cyclists, but they are fast. I spot them after four hours of protesting in which I held up the back end of the march with the other bikers. We block a police car with our bikes. A white lesbian named Kay bosses me into this job. I don’t mind it, but she wants to talk a lot and I get tired pushing the bike and watching the cop car and listening to Kay. Whatever, white people problems.

Sometimes the cop car and I are side by side, and whenever I look into the window, I see a young white woman, hair in a ponytail, shoulders tensed over the wheel. She doesn’t look back at me. Eyes straight ahead. This is something I hate about the police at these protests. The way they look past you, over your head, anywhere but your face and eyes. Or they have dead eyes, like you don’t register.

My knees hurt, my shoulder hurts, my robot hasn’t been working so I’m typing too much. Not taking care. I should go home.

“No justice! No peace! No justice! No peace!”

But they whiz up Fourth Avenue, and I instinctively turn toward them and pedal hard. Catch up, I say to myself, catch up.

They shout, “No justice! No peace! No justice! No peace!”

We take up the whole street and I pedal as hard and as fast as I can, but I’m still falling behind. I let myself slow down and slide over to the curb, where I rest my foot and root around for my phone in my backpack.

What am I looking for?

No one’s texted me.

Check email. Check Twitter. Check Facebook. Check Insta.

More bikes trail past. I zip my phone away, check over my shoulder, and push forward. My weaknesses are everywhere: car doors, double-parked cars, and buses. Buses scare me. Also squeezing between a bus stopped at a light and a parked car. I’ll sit in bus exhaust rather than do that.

I pedal west after them, toward the river. The sun is setting over the Hudson, gleaming onto Fourteenth Street and into my eyes. I can’t see. I squint, slow down, coast.

“Whose streets? Our streets! Whose streets? Our streets!” the cyclists up ahead of me chant.

I see the pothole, really a small crater in the asphalt, for less than half a second. My reflexes are too slow, and so my front tire plunges down into it. I grip my handlebars tightly and stiffen my arms. My backpack flies out of my front basket and for some reason, I try to grab it. The bike turns to the right and into what I know might be traffic behind me. This is it, I think, I’m dead. The sun is still shining in my eyes as the tire lodges itself in the hole, and then a second later pops out. Miraculously, I don’t topple over. But then I run over my backpack. My lock, also in the basket, jumps out onto the road, and I run over that too. I feel the bike seat between my legs. It hurts. I stop. My legs shake and I get off the bike, pick up the lock and my backpack. I fish my phone out of the front pocket. It’s cracked.

“Fuck,” I say to no one, because the street is actually empty.

I press the home button. It works. Seemingly.

I walk my bike home. Legs shaking. Sore pussy.

Dark Times

When I am falling in love with Eurydice, I worry that someone will hurt her. People fuck with her a lot. They say, “What are you?” when she drops off deliveries. Sometimes a creep tries to lure her into his apartment.

“Just come in for a second. I gotta hunt around for your tip.”

“I’m fine out here,” she says.

One time, she loses her phone and I don’t hear from her for two days, and I’m sure she’s dead. I text her one friend that I know, and she says, “Haven’t seen her, but I will ask around.”

She shows up sheepish with no phone, crying. “I tried to see my kids and my ex wouldn’t let me, and then I went to Cubby and got so drunk, they threw me out.” I say a bunch of useless, angry things about her ex, and she sobs. I feel terrible when she cries, and I cry too.

“Trans women still lose their kids you know,” she says.

“I know,” I say stupidly, uselessly.

I feel like she leaves parts out of the two-days-missing story, but I don’t press her. I just say, “You can tell me anything. You can also have secrets.”

She falls asleep for twenty-four hours, wakes up with a fever, and I beg her to go to Callen-Lorde.

But she won’t. We wait it out, and then she wakes up after another half day as if nothing happened.

“I don’t want to talk about it, babe,” she says. “I want to live in the moment, with you.”

I nod, something lodges in my heart, and I ask her if she wants Taco Bell, her favorite. “My treat.”

Gina carries a knife from when she was in Iraq and so I worry less about her. But I don’t think it’s good that she won’t leave her house, and sometimes I know it’s fear that keeps her inside too often. She says she doesn’t want to get “clocked” or read the wrong way, and Picasso worries about this too.

“This book is set in a dark time, a changing time. I can’t always keep up.”

Picasso doesn’t acknowledge very many people, but I see the way people look at us in certain places. They are trying to figure something out. One day, before the virus, he says to me, “If I have to go back to Brazil, I will. If your country doesn’t get it together, I can do that.”

Is my middle-aged, white, cis face protection? Likely.

If you love trans people, if you have trans friends and lovers, you worry because of what can happen. Just like you worry for your Black and Brown friends, because America is so violent and racist and it’s a dark time. Or you worry for yourself and your family because you are Black, Brown, Asian, queer, trans, and/or disabled.

This book is set in a dark time, a changing time. I can’t always keep up.